Oregon Beaches Aglow with Freaky Critters - About Oregon Coast Dinoflagellates

Published 2006

By Oregon Coast Beach Connection staff

(Oregon Coast) – The word is getting out about this interesting and rare phenomenon: “glowing sands” is being spotted all over the Oregon coast this summer. (Above: look for dark beaches at night, with no light interference, like this one at Cannon Beach).

BeachConnection.net first gave it major attention about two weeks ago, spotting it in Newport, Arch Cape, Cannon Beach and then Nehalem Bay. Those sightings, in turn, got attention in other local papers on the coast - and thus the buzz has begun.

The key is a tiny, microscopic creature called a dinoflagellate. They are essentially tiny plants – a form of phytoplankton, which, like all phytoplankton, are the base of the ocean’s food chain.

During the last four weeks, they’ve been spotted on and off on Oregon’s beaches, giving off a faint bluish green and brief spark when stepped on or if you kick the sand around.

They vary in intensity and effect. One night in July in Arch Cape, they yielded enormous showers of them when the sand was disturbed. Two nights later in the same spot, they were much less prominent. Rockaway resident Abby Olson, who saw them in Arch Cape that night, said she scuffed her foot on the sand in one spot and a three inch-long section of sand continued glowing, albeit faintly, looking like a glow stick.

They were also spotted in Newport’s Nye Beach, although very faint in most spots, making them hard to see.

At Nehalem Bay, they create an eerie glowing trail behind your hand

In Manzanita, BeachConnection.net staff saw them twinkling in the water of receding waves, as waves heading backwards kicked up the sand they were embedded in.

They are also sometimes seen in pools of standing water further up the beach from the tide line, where they will often look like small galaxies that briefly explode into existence.

In bays, like Nehalem Bay, they give off an eerie, blue, glowing trail as you move your hand around in the water. Locals there who go swimming in these waters during the proliferation of dinoflagellates say it “makes your body look like a glowing skeleton.”

It’s an awesome sight, one that sends squeals of joy and surprise out of those who see it for the first time.

Rachel Thompson, a Nehalem resident, was introduced to the phenomenon by BeachConnection.net editor Andre’ Hagestedt. “That was so cool about the beach glow,” she said. “I had so much fun. I went out a couple days later and it wasn't as strong of a glow. Still pretty amazing though.”

The occurrence of dinoflagellate blooms coincides with certain weather and oceanic conditions, which tend to happen more often in the summer. It is slightly rare here on this coast, as Oregon’s climate doesn’t allow them as much as warmer places like California. In Puerto Rico, there are numerous bays that are famous for containing a lot of the tiny critters, creating glowing bays.

Here, they change and shift with the winds and currents, making them even more rare. They can appear one night, and then not appear again for months. And then they don’t live in the sand more than a day.

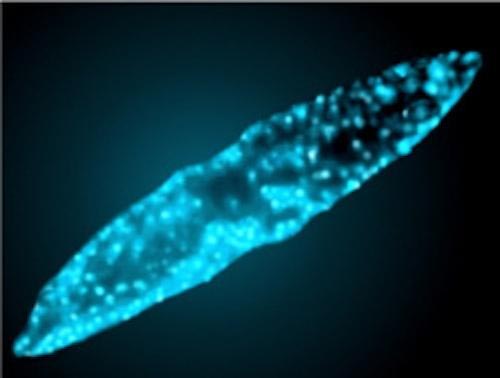

Above: glowing phytoplankton is almost impossible to photograph on the Oregon coast. This shot, taken in 2016 shows some dots which are dinoflagellates, while most dots are camera pixel noise.

Locals on the north coast have called it “star stompin’,” while most incorrectly refer to the phenomenon as “phosphorescent sand.” These creatures are more like fireflies and are bioluminescent, meaning they give off light through their own body chemistry, whereas phosphorescence is a chemical reaction by itself, created by nonliving elements of nature, having nothing to do with living organisms.

These critters off our coast are reliant on sunlight for their glow, said Tiffany Boothe, of the Seaside Aquarium.

“Many dinoflagellates are photosynthetic and play a key role as producers in the food chains of the ocean,” Boothe said. “The luminescence of photosynthetic dinoflagellates is very much influenced by the intensity of the previous day’s sunlight. The brighter the sunlight, the brighter the luminescence will be. Bioluminescence in dinoflagellates reaches its maximum levels two hours into darkness.”

“Dinoflagellates are the most common source of bioluminescence and are also known as Pyrrophyta - or fire plants,” Boothe said. “Dinoflagellates are unicellular and are usually planktonic. 90 percent are marine plankton. They are microscopic and mobile. They swim by two flagella, which are movable protein strands.”

Look for wet sand, not dry sand, to see the tiny flashes (pictured: Lincoln City)

It’s a warmer than usual summer in many ways, which can cause weather conditions on the oceans that create “upwellings” – the upsurge of colder waters from the deep that bring the nutrients and thus make for larger blooms of dinoflagellates.

Boothe said that ironically, it’s the colder waters that bring out more of the glowing beasties. “The colder waters from the deep cause the blooms, because they bring the nutrients the dinoflagellates live on, making them reproduce in huge numbers.”

Jim Burke, Director of Animal Husbandry at the Oregon Coast Aquarium in Newport, described it further.

“This time of year there are upwelling events that bring nutrient rich waters to the surface,” said Burke. “These waters are then the cause of plankton blooms. These plankton blooms consist of many microorganisms, many of which include the bioluminescent dinoflagellates. When these dinoflagellates are agitated, a chemical reaction takes place that releases light.”

He said warm summers like this one create north winds, which then bring the upwellings.

Burke said he didn’t know the biological reason for dinoflagellates being bioluminescent, but said that the reason larger creatures like some jellyfish give off such a glow is so they can attract prey.

The luminescence of a single dinoflagellate lasts for 0.1 seconds, which is why photographing the phenomenon is so next to impossible. Larger organisms, such as jellyfish, can be luminescent for tens of seconds.

Closeup of a glowing phytoplankton courtesy Dr. Edith Widder

Boothe tried to photograph them in early August in Gearhart, but to no avail. She and two friends grabbed jars and poured wet sand that had the dinoflagellates into jars. They then tried shaking the jars. But the flashes happen too fast for a long exposure to catch – and a long exposure is what it would take to catch such a faint glow. Oregon Coast Lodgings for this - Where to eat - Maps - Virtual Tours

“Bioluminescence is the light produced by a chemical reaction that occurs in an organism,” said Boothe. “It occurs at all depths in the ocean, but is most commonly observed at the surface. Bioluminescence is the only source of light in the deep ocean where sunlight does not penetrate.”

Boothe said bioluminescence in sea creatures is blue for two reasons. One, blue/green light travels the farthest in water. “Its wavelength is between 440 to 479 nm, which is mid-range in the spectrum of colors,” Boothe said. “And the second reason is that most organisms are sensitive to only blue light. They do not have the ability to absorb the longer or shorter wavelengths of other lights such as red.”

Chances are decent you’ll see it at least one more time in summer, but fall’s “second summer” on the coast often brings it in greater numbers. This is when conditions on the coast are at their warmest, happening September and early October.

They have also been seen glowing a faint blue on waves that hit rocks in the night.

Cannon Beach Lodging

Nehalem Bay Lodgings

Manzanita Hotels, Lodging

Three Capes Lodging

Pacific City Hotels, Lodging

Lincoln City Lodging

Depoe Bay Lodging

Newport Lodging

Waldport Lodging

Yachats Lodging

Oregon Coast Vacation Rentals

Oregon Coast Lodging Specials

More About Oregon Coast hotels, lodging.....

More About Oregon Coast Restaurants, Dining.....

Back to Oregon Coast

Contact Advertise on BeachConnection.net

All Content, unless otherwise attributed, copyright BeachConnection.net Unauthorized use or publication is not permitted