Cape Meares Lava Flows - Oregon Coast Attraction Tells a Frightening Geologic Story

Three Capes Loop Virtual Tour, Oregon Coast: Oceanside, Netarts, Tierra Del Mar, Pacific City

(Oceanside, Oregon) – The sheer wonders (and the terrifying truth) of how the Oregon coast came to look as it does are on display at Cape Meares, just west of Tillamook. This dramatic set of cliffs is a several miles northwest of the village of Tillamook, and just a tad bit south of the Bayocean Spit - which itself boasts a weird history of having once been a major resort town, but is now only a stretch of sandy dunes.

Cape Meares has a bundle of attractions all its own: the wacky, candelabra-shaped “Octopus Tree,” a major haven for watching birds or storms, a prime place for spotting whales, and a lighthouse. But its soaring, black cliffs are also a catalog of freaky, geologic activity that goes back some 15 million years, and tells some scary tales that make the spookiest horror films look like early Disney flicks.

Looking at the massive cliff walls and their ragged features from the various viewpoints along Cape Meares is, understandably, one of the big pastimes at this amazing spot on the north Oregon coast. But if you know how to read it, a wild saga emerges. They are, in many ways, a slice of the Earth’s crust in this area, cut down the middle so we can – quite literally – see the layers.

Layers of volcanic activity are seen in the various lines of the cliff walls

Tom Horning is a Seaside resident and renowned geologist on the subject of anything coastal.. He’s spent considerable time gazing at the myriad of layers embedded in the rocks here, frozen in time from the Miocene period. He says these layers represent eons of massive lava flows that have piled on each other over millions of years, coming here from hundreds of miles away.

You can see the lines along the cliffs here, which show one lava flow upon another, until you get to the topsoil, which is its own story.

He says it all begins with a fiery situation over 15 million years ago, when a giant hole in the Earth’s crust spewed so much lava it scarred and seared its way across what was then Idaho and Eastern Oregon, until it reached the sea (which was several miles inland, perhaps as much as 75 miles east).

This is the same hole that now fuels the action at Yellowstone National Park. Continental drift pushed that weakness in the crust eastward over time, and it now lies there. See more on this here

These huge invasions of lava are called the Columbia River Basalt Flows.

“Cape Meares is a lava delta where Columbia River Basalt Flows filled a canyon that had been eroded into the coastal hills,” Horning said.

This wouldn’t have happened in the quite the same way if it wasn’t for the coast range being so diminutive at the time. The lava intrusion followed the path of an ancient river, over the still small coast range.

“Before the coast range had risen too much, the Cascades rivers flowed westerly into the ocean via several major valleys, and there wasn't a Willamette,” Horning said. “It formed when the rivers couldn't cut down faster than the coast range could rise, and the rivers were sundered and forced to flow backward to the east. But before that happened, the Columbia River Basalts flooded down the Miocene Columbia Gorge, then located near Mt. Hood, and spread out across the coastal plain/proto-Willamette Valley, thence to the ocean via major rivers.”

At that point, Horning said the river path the lava followed was that of the Trask-Tualatin, which possibly extended into the Cascades as the Clackamas River.

Essentially, these massive flows came again and again, separated by hundreds, thousands or maybe even millions of years. No one is really certain how long between each eruption. The lava flows literally filled up the space in a prehistoric valley, locking its shape in time with the sturdy basalt rock that happens after lava cools. Eventually, that valley eroded away, leaving only the rock.

Some time after the last eruption, the massive rock structure sank into the Earth and popped up again, several times over the millennia as the land rose and fell. Sometimes, depending what the ocean was up to that particular epoch, it sank into the sea, occasionally becoming the sea floor.

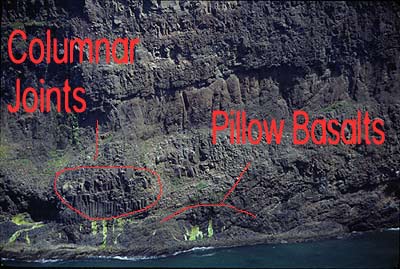

If you look at the bottom of the cliffs, you some different formations, rather than the jagged, undulating lines of various lava flows you see throughout most of the cliffs. This is the beginning of the flows.

Horning refers to the various layers as units, and notes the presence of pillow basalts at the bottom of the cliffs. These kind of basalts are puffy and rounded, happening when lava hits the water and cools abruptly.

Horning refers to the various layers as units, and notes the presence of pillow basalts at the bottom of the cliffs. These kind of basalts are puffy and rounded, happening when lava hits the water and cools abruptly.

This cooling mass of water could have been the sea, or it could have been the river water the lava flows were marching through. (Photo at right by Horning)

“The lower flow units include pillow lavas and coarse basaltic gravels that built out a delta in the valley,” Horning said. “As time passed, the lavas filled above sea level and no longer accumulated as pillows and gravels, but instead as sheets of lava flows that cooled in the air.”

This cooling in the air action sometimes created strange shapes, which can also be seen at the bottom of the cliffs: little bundles of what look like columns dotting throughout one layer. This is when the lava cooled from the inside upward, and the cooled sections of lava separated into these upward-pointing shafts.

“At the bottom, you will see cross-bedded gravels and pillow layers,” Horning said. “Near the top, you will see lavas with nearly vertical cooling joints in the flows. They can interfinger or interlayer, depending on water levels. Sometimes, lavas can squeeze in between deeper layers to cool as sills, with vertical joint systems that look much like columnar jointing of lava flows. The whole complex has been tipped to the west by about 15 degrees, so its eastern part has been lifted high into the sky.”

There are surprises like sea caves in these cliffs too

Hence the different and odd shapes you see in this cross section of geologic wonders.

Horning said there is lots to be discovered still about all this process and about how this area looked over those millions of years. Unfortunately, so much is gone.

“Its connection to the Willamette Valley has been eroded away,” Horning said. “The trick to seeing the river channel coming through the coast range is to connect the sources of the Trask and Tualatin Rivers. They meet at the summit of the coast range."

Finally, the sandstone layer at the top of this delightful cross section has some connections to areas on the central coast.

“The sandstone atop the cliffs was laid down over the basalts,” Horning said. “It is called the Sandstone of Cape Meares. It correlates down the coast to the sandstone at Depoe Bay’s Whale Cove, which also forms a distinct layer near Depoe Bay. It was deposited in 100 to 200 ft deep water in the ocean - based on storm-caused hummocky cross bedding in the sands and the presence of marine fossils.”

The origin of this top layer is quite a ways east, Horning said, carried down to the ocean via the prehistoric Columbia from Idaho and Washington, during the Miocene age. The Whale Cove sandstone is from the same period.

“At Depoe Bay, it is overlain by the Frenchman Springs basalt, one the last large lava flows leaving the Chief Joseph Dike Swarm near Lewiston, Idaho, that was large enough to flow to the ocean,” Horning said. “Little of the capping layer of Frenchman Springs lava remains at Cape Meares, but there is a small mass at the summit of the hill, east of the coastal road.”

It’s all a part of a bigger, weirder picture that helped form what we all see on the coastline. The origin of Oregon’s most stunning tourism attraction is really quite a frightening tale.

“Put the world's largest lava flows into the submarine delta of one of the world's largest rivers, in the world's largest ocean, along one of the world's largest fault zones - and you get the Oregon Coast,” Horning said. “The processes are huge and the scale of the system is immense. It is almost too impressive to comprehend.”